Computer Animation – Assignment 2

Uses of GIFs [P3]

The GIF (Graphics Interchange Format) is a type of image used primarily on the web, developed by CompuServ, end released in 1987. The format was used extensively on the web until the introduction of the PNG (Portable Network Graphic) format, as it supports transparency. When the PNG format was released in 1996, designers were able to use alpha transparency, meaning each pixel of an image could assume any of 256 levels of opacity, whereas with GIF each pixel was either opaque or transparent. GIFs were used for icons on websites even after the introduction of PNGs, but are now primarily used for their animation capabilities.

Examples of animated GIFs, showing optical illusions using the theory of the Penrose triangle.

Examples of animated GIFs, showing optical illusions using the theory of the Penrose triangle.

Animation was introduced to GIF images with a secondary version (named 89a, as opposed to the original 87a), which was released in 1989. This led to a huge number of animations to be created, and a new community to emerge on the web. GIFs could suddenly be used to tell short stories, and quickly people began to distribute them widely. Soon after, browsers started to support the animated images and in turn make the sharing of GIFs even easier. This is now standard in all major browsers, at the desktop and on mobile. Because of this support offered for animated GIFs, they are one of the most compatible ways to show a motion graphic on the web.

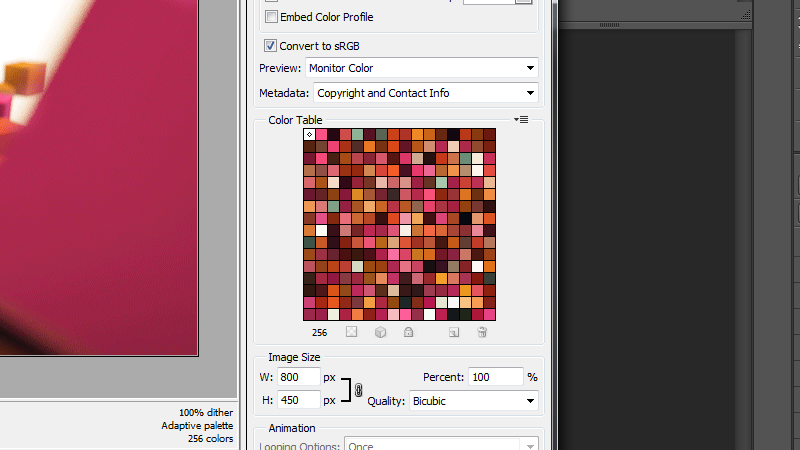

GIFs are known, however, to be inefficient for sharing animations, as the file sizes of animated GIFs are usually large given their dimensions and number of frames when compared to more advanced formats such as WebM video and better compression codecs. They are also limited by the number of colours that they support. Each GIF image can only display up to 256 colours, but these colours can be chosen from a palette of over 16 million. Applications that can create as GIFs, such as Photoshop, will typically evaluate the image and pick the 256 most useful colours in order to maintain quality. A technique called dithering will also likely be used, meaning gradual changes in colour will be a lot less noticeable.

GIFs are also limited when it comes to transparency. If a user wishes to include transparency in an image, one of the 256 colours picked for the image will have to be sacrificed. This is because transparency is considered a colour in the GIF format, unlike with the PNG format in which transparency is encoded using an alpha channel.

There is a lot of controversy over the pronunciation of the formats acronym and common name. The majority of people pronounce the letters as would seem standard, using a hard g sound. Others compare the name to that of the peanut butter brand Jiff, claiming that it was the intended pronunciation as clarified by the author of the format. When he was presented with a Webby Award in 2013, he generated a huge response on Twitter from his reiteration that most were pronouncing the name "wrong".

HTML/JavaScipt/SVG and Flash: A Comparison [M2]

On the web, animations have a great number of uses. Perhaps their most common use is to show activity as a page or resource is loading. Although rare on the modern web, loaders can still be seen when viewing more data intensive media, such as video or large images. GIF animations are used extensively on image sharing websites such as Imgur, often showing short clips made by users or from popular films and TV shows. A lot of animations have been uploaded to YouTube too, and communities have emerged of people sharing their creations, usually created In Adobe Flash Professional.

A logo comissioned by the World Wide Web Consortium to represent the HTML5 specification, which includes additions to HTML, CSS and JavaScript.

A logo comissioned by the World Wide Web Consortium to represent the HTML5 specification, which includes additions to HTML, CSS and JavaScript.

HTML, JavaScript and SVGs

Although the SVG, or scalable vector graphic, format was introduced in 2001, it's only in the last few years that the developers of the major browsers – Google, Mozilla, Microsoft, Opera Software and Apple – have put effort towards fully supporting the file type. The format allows webmasters to embed vector images in websites and, thanks to their XML architecture, modify them with JavaScript and style them with CSS. Using delayed loops in JavaScript and mathematical interpolation, SVGs can be animated, leading to a very rich experience. Used in conjunction with parallax scrolling effects and responsive design elements, a very impressive effect can be created, as shown excellently by the Garden web design agency's portfolio website.

Despite the advantages of animation using SVG, they are still not common on the web, and are typically found on a select few tailor-made websites. SVG animation is also in early days, and although SVG animations are very efficient, perform well, and offer much better browser support than Flash, the possibilities are somewhat limited. SVGs were not created with the intention of being used as a medium for animation, and JavaScript does not have animation functionality by default. SVG animation usually consists of gradually changing stroke and fill parameters on particular paths. Unlike in Flash, in which each frame is stored separately, SVG animations are able to play at the highest framerate supported by the device showing them.

In order to create animations and websites to display them, all one realistically needs is a modern web browser and a good text editor. There are plenty of tutorials online, and the documentation provided by the W3C and by Mozilla via its developer network is detailed and easy to work with. Graphical software can also be used to ease the creation of SVGs that can then be animated.

Flash

In order to create Flash projects, one realistically needs tailor-made software. Although free alternatives do exists, Flash Professional is the industry standard application, developed by Adobe alongside the Flash specification and player. This was previously all developed by Macromedia, but Adobe acquired the rival in late 2005. The need for software behind a pay-wall makes the format a lot less accessible to the majority of budding designers, forcing them to either spend more than they're comfortable spending; pirating the software and consequently breaking the law; or using sub-par software which would likely have a negative impact on their workflow and productivity. Free alternatives include programs such as Synfig, advertising itself as open-source animation software.

A completed game or animation made in flash is typically exported from Flash Professional as an SWF. This is a small web format object, which can be embedded on websites using HTML or viewed using a standalone player or web browser. In order to view Flash objects, in order to play games or most video on the internet, one must have a plugin installed for their browser, otherwise it must be built in. In the case of Internet Explorer, the Windows version of Flash will suffice. Chrome instead comes packaged with a third-party Flash player called PepperFlash, which aims to perform better than the official Adobe software. By including its own players, Chrome also brings flash support to Linux, which Adobe ceased to support in February 2012. This requirement to have extra software installed just to view some web content makes the use of Flash undesirable; many developers and enthusiasts frown upon the use of Flash on the web. The dependency on software that is gradually losing support from Adobe is pushing browser developers to implement HTML5 and CSS3 specification, and the usage of Flash is quickly declining.

Versus

Advances brought by HTML5 nullified many of Flash's advantages by providing more up-to-date and compatible replacements. On the modern web very few tasks truly require Flash. Although the vast majority of games are still written in Flash, these could be written using HTML5 technologies. One of the most prominent features in Flash still in use is the ability to copy information to the system clipboard, which is required by websites offering a "copy to clipboard" button for a particular piece of information. This is not available using HTML and JavaScript as it presents a security flaw to an ever-more hostile web.

Animation Tools in Software [P4]

Layers are used in a number of different applications, and not just in animation. Vector and raster image editors often make use of layering to keep a file easy to manage and change. Layers are effectively sheets laid on top of each other, that are generally transparent by default. A way to visualise this physically would be the use of acetate, mentioned in the cel animation part of Assignment 1. Layering makes the separation of inked lines, shading, highlighting, colouring and motion effects much easier for the animator and it's coincidentally very important in creating an efficient workflow.

Frames are individual images, that when shown for short periods of time in quick succession create an animation. They are the basis of animation, and can be generated by hand, as per tradition, or using software such as Flash Professional or Cinema 4D. In many software packages aimed at animation, one can create 'tweens too. This involves creating two "keyframes" which mark significant turning points in the animation. The software will then use interpolation to work out a smooth path between the two, which often creates a better final product than drawing each frame individually.

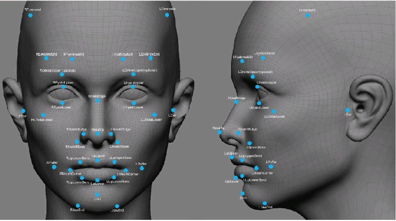

An image of 3D animation software, showing control points on a face.

An image of 3D animation software, showing control points on a face.

Controls in 3D animation are points on a model that can be easily moved to change the appearance of an object. Typically used for animation of faces, people or animals, controls make for much more consistent movement in characters, and make animation easier. The word is also used to refer to buttons that cause a work-in-progress animation to play, pause, rewind, fast-forward, etc.

Buttons, used primarily in Flash, allow a designer or developer to take input from the user. This refers less to animation and more to 2D games and applications in Flash. Buttons can be clicked by a user, triggering ActionScript code in the Flash object to fire.

The Library in Flash Professional, or perhaps the Content Browser in Cinema, allows the animator to browse the content that has been created in or imported into the project. This makes management of symbols, audio, animation, scripts and other assets easier, and is integral in building Flash applications. Most often items can be dragged from the library onto the stage or into a 3D environment, making them easily accessible.

Symbols are used in Flash to make the movement of particular objects more simple. Drawings, images or video clips can be defined as a symbol, immediately appearing in the library. This makes their re-use more simple, and they can be inserted into different documents or even different projects with ease. Symbols are also kept separate from other items on their layer, preventing loss of work and improving workflow.

As assets are loading, preloaders are often shown by Flash applications or games. These are often short animations or progress bars showing the rate of loading. In order that they can be quickly loaded themselves and displayed as the remaining assets download, they must be small digitally, and stereotypically take the form of a small, short spinning animation.

In Flash, scripting using a dialect of ECMAScript known as ActionScript can be used to make interactive content. Scripting is essential in games, for example, taking care of the backend logic and processing of data. ActionScript allows developers to bind actions to events such as key presses or mouse clicks. The JavaScript like syntax of ActioanScript also makes it familiar to many people, and makes for more consistency across programming for the web.

Integration refers to the inclusion of a number of different types of file in a Flash project. Flash was used extensively to create video players for websites, but this is now becoming possible using the HTML5 alternative. For this use, Flash would require integration of a video file, in the MP4 format, for example.

Preparing Animation for the Web [P5]

When creating animations for the web, a number of techniques are used to make the content more suited to it's environment and purpose. Flash was used a lot on the web in previous years because of the rich content creation it enabled. For example, a lot of websites used Flash for buttons that would react when hovered over, something that can now be done far more efficiently with CSS3 or even JavaScript.

Support

Browser support for different formats of media is big factor in deciding what can be reliably used. Flash, for instance, is supported out-of-the-box only by Google Chrome. Other browsers require a Flash player plugin, and Adobe's support for their own is gradually diminishing. Flash cannot be relied on for anything of importance, and its use is discouraged by the majority of professionals in the field of web design and development.

Mobile browsers and Internet Explorer are infamous for offering poor support for new web technologies. HTML5 and CSS3 are still considered to be new, potentially unsupported standards, and many believe their use should be regarded as somewhat unreliable. Although mostly supported by the majority of browsers, particularly on the desktop, there are often caveats that make specific CSS3 rules, for example, unusable.

In reality, HTML5 and GIFs are the only way of showing video animation, asides from a standalone, native app. That said, simple animations can theoretically be made with standard HTML and SVG, animated with JavaScript, should the browser support it. For example, the version of MobileSafari package with iOS 4.2.1, despite supporting most of HTML5 at a time when support was minimal across all browsers, barely supports SVGs. GIFs, on the other hand, although boasting better support than SVG, have performance issues. As the data is virtually uncompressed, and the format encodes data inefficiently, it requires more graphical processing power to display. Most mobile devices made before ~2012 didn't have this power, and GIF animations suffered as a result. The poor support for web technologies during the early years of smartphone popularity also led to many developers building native software for mobile operating systems rather than web-based applications.

Data Transfer

File size must be considered when using animations on the web. Flash objects and GIFs both cost a lot of data to use, which could be an issue for people browsing on mobile data plans that charge fees for exceeding small monthly download caps. The more data that must be loaded for the page to function, the longer the page will take to load as well, and the need for preloaders on a website is frowned upon.

GIFs, for example, are barely compressed, meaning more data must be processed in order to display the image or animation, and more system memory is filled as a result. This can result in an animation whose performance worsens as played. HTML5 video, on the other hand, offers many different compression formats. The <video> element supports OGG Theoris, MPEG-4 and WebM video, each of which offer several compression options. Compression not only vastly reduces the size of the output video file and therefore the data that must be transferred, but improves the performance of the video on the device playing it. This is important for less capable devices such as mobile phones and media players.

Compression of Animation [M3]

An image showing the effect of heavy JPEG compression (left) to minimal compression, near lossiness (right).

An image showing the effect of heavy JPEG compression (left) to minimal compression, near lossiness (right).

As animations are essentially a number of images played in quick succession, similar compression algorithms are used in video as for still images. The primary difference is the opportunity to preserve parts of the image between frame changes, and only update the part of the image that is required to change. Compression methods for images and video can both be categorised as either lossy or lossless, based on whether or not the video is identical in quality to the original, after having been compressed. Lossy image formats include the popular JPEG algorithm, used on the majority of digital photographs. An example of a lossless image format is the PNG (portable network graphic) filetype, often used on the web and designed to replace the GIF format for storage of computer graphics.

JPEG algorithms are often used for video compression, and prove significantly more effective than when compressing each frame individually. This is because in typical footage, the majority of the frame stays the same, whole a subject or part of a subject moves. This means that most frames can be encoded to duplicate the previous frame, save for a particular area. The GIF format does not use this fact to its advantage, and as a result the digital size of GIF animations suffers. Instead, each frame is entirely separate from any other, and each is encoded from scratch. This means the exact same data may be written in the file several times, which needlessly increases the file size. GIFs are also only able to store up to 256 colours, meaning they only offer lossy compression for the vast majority of animations.

Optimisation

In order to minimise the amount of data that must be stored, compressed or not, a variety of optimisation methods exist. Generally only considered in extreme situations, frame disposal can be used to lower the number of frames to be stored. A typical animation or movie plays at 24 or 30 frames per second, but some higher. Slow motion footage, for example, can fill a camera's storage card in a matter of seconds when recording at a high definition. The footage recorded, however, could potentially have a framerate in the thousands, which would allow the footage to be slowed down by several magnitudes. For a clip recorded at 1200 frames per second, 10% speed would still leave the output at 120 FPS. This could then be optimised for video by removing three of every four frames, bringing the output down to just 30 FPS. This would have no noticeable effect to the human eye, but would meant that only a quarter as much data would need to be encoded.

Auto Crop

When editing photos or creating computer graphics in an application like Photoshop, or when creating a composition in video in post-production software lie after Effects, objects may become scattered over an otherwise transparent canvas. In order to trim the canvas down in order that it only covers area which has objects in, auto cropping might be used. This takes the layer selected by the user, and finds a rectangle as large as possible within it that is comprised entirely of 0% transparent pixels, meaning that the final product is a cropped version of the original, in which every pixel is entirely opaque.

Scaling

Files can be scaled digitally to reduce the physical area they consume. Because images and film clips are two dimensional, halving the frame width and height will leave only a quarter of the pixels hat were originally in the image. In order to be left with half as many pixels, one must instead multiply each dimension by ~70.1%, or half of route-two, in order to maintain proportions. Some screens also have rectangular pixels instead of usual square pixels, which must adjusted for in order to prevent horizontal or vertical stretching.

Selective Palettes

File size can also be reduced by using a more conservative colour palette. Similarly to GIF's support of no more than 256 colours per image, one PNG format variation, called PNG-8, can also be configured to use a smaller palette. When exporting PNGs for the web from Photoshop, for instance, one can select from different colour palette profiles, including Adaptive, Selective and Progressive. The profiles alter how the program picks the small permitted palette based on the image itself. Although a limited number of colours may be selected, each chosen colour can typically be any of the ~16.1 million representable using RGB.

Using a more selective palette, 16 colours for example, each pixel can be encoded using only 4 bits (24 = 16). Near the beginning of the image file, the 16 colours that have been picked for the image are assigned a digit between 0 and f, which can then be used to refer to the colour in the actual image data. This is considerably more concise than a six-digit colour code when potentially millions of pixels are concerned, and leads to a smaller file. The use of a smaller colour palette, however, has a noticeable effect on the image. Posterisation is often visible if dithering is not used, which makes changes between areas of different colours more obvious.

Adobe Flash Professional and Maxon Cinema 4D: A Comparison [D1]

Introduction

The logo used for Cinema 4D since Release 13.

The logo used for Cinema 4D since Release 13.

Since the first feature-length films were created solely using computer generated imagery, thousands of other cinematic features and shorts have been created digitally. In order to aid this process and to develop our knowledge of computer science, software packages have been developed by many different companies and groups. For purposes of comparison, we will look at Adobe's Flash Professional and Maxon's Cinema 4D Studio, both professional-grade animation applications.

Dimensions of Media

Firstly, Flash Professional is used solely to create two-dimensional media. Transformations can be used to create the illusion of objects moving in three-dimensional space, but genuine 3D support has not been implemented into the software itself. Flash is used primarily to create advertisements now, and therefore does not require support for a complex 3D environment. Flash is also reaching the end of its lifespan, seeing progressively less use on the web, meaning 3D support would not be worth developing for Flash – the format or the application.Although Flash does not support three-dimensional objects, a similar format called Shockwave, also developed by Macromedia and now Adobe, does. Most commonly used to create games for the web in 3D environments, Shockwave was sometimes confused with Flash as SWF (the file name extension used by Flash objects) initially stood for Shockwave Flash. The Shockwave format is an entirely separate type of media, built using Adobe Director, a now fairly unused software package.

Cinema 4D, alternatively, is based entirely in three dimensions. The 4D in it's name refers to the use of time in the application, as it is an animation-centric program, despite it's advanced capabilities in 3D modelling. The program allows user to very quickly add primitives – simple shapes like cubes, cylinders, spheres and platonics – to the scene. The user can then change a series of parameters describing the object, such as radius, height, width, rotational segments and fillet cap radius (chamfer).

Interface

The UI (user interface) of Flash Professional is similar, certainly in style as well as layout, to most other industry-grade Adobe applications. The tools are situated in a panel to the right of the screen, and the timeline is found below the stage, similar to a canvas in Photoshop. The timeline is clearly divided into frames, and can be scrubbed through by dragging the playhead horizontally. Drop-down menus can be found along the top of the window, giving access to basic files commands such as save, open and close, as well as more complex tools. Using a lighter-grey background, the application is not as suited as others to being used for long periods of time.

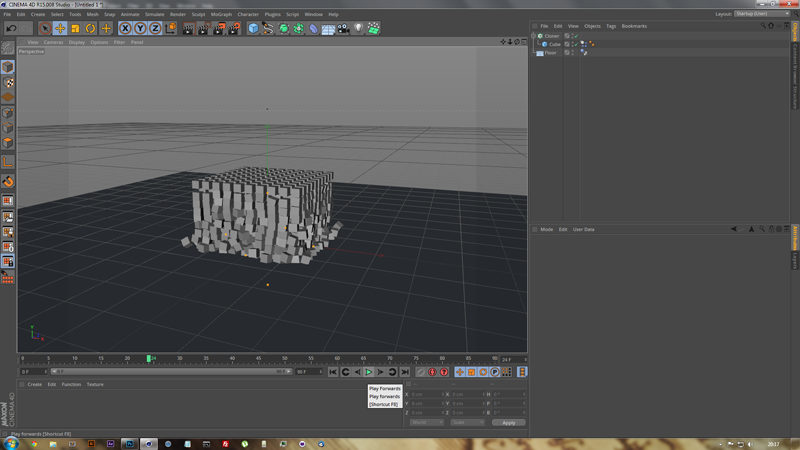

An example of the Cinema 4D interface, which can be havily customised. In the scene is a pile of one thousand simulated cubes.

An example of the Cinema 4D interface, which can be havily customised. In the scene is a pile of one thousand simulated cubes.

Cinema 4D is very easy to learn to use, and although it may seem daunting when first opened, the complex UI in fact just gives quick access to a great amount of tools and options. Customising this UI is also possible, and in many different ways. Panels can be moved around the screen, brought to windowed mode, deleted and created. The size of different UI icons can be changed, and the font used throughout the application can too, not to mention the colour scheme. This customisation allows an animator or modeller to mould their digital workplace to their needs and wants, putting the tools they use most where they can easily find them. This is important to many, and the extent of customisation beats even that of the newest Adobe Creative Cloud programs.

In comparison, both applications offer comprehensive interfaces, and both give the user the power to rearrange the items. That said, the customisability in Cinema 4D is a lot higher, and does not attempt to be as simple and user-friendly as Flash Professional's. From personal experience, I prefer the UI in Cinema to any Adobe suite application's, not just because of the customisation opportunities, but because of how much more intuitive it is to use. As an example, in any mathematical input box, Cinema with accept an expression such as 150 * 3, and will calculate the value automatically. This may seem unimportant, but when using a vector-based program, it makes modification of values based on what they already are a lot more simple.

Vector and Raster

An image showing the difference between vector and raster based imagery when displayed on a large scale.

An image showing the difference between vector and raster based imagery when displayed on a large scale.

Flash is, at heart, a vector based program, but that supports raster artwork proficiently. This means that the program, by default, handles shapes and drawings as mathematical data that is read as instructions to plot the image, while also supporting pixel-based artwork; that which is stored as hundreds of cells each with it's own colour. Creators are able to import images and video into the program in many different formats, and use them as assets. Most of the games built using Flash are based on raster sprites, and with everything considered, all media will eventually be displayed as pixels anyway. The vector aspect of Flash is still important, however. Text can be resized and freely transformed without any loss of quality, which is useful in animation. Vector storage offers better quality (truly lossless) when scaling or transforming and consumes less space digitally, but they cannot realistically be used to encode photographs or imagery with complex shading.

Cinema 4D, similarly, is vector based, but offers support for raster graphics in an entirely different way. The objects in a scene are handled as mathematical data, making the project files (.c4d) considerably smaller, and reducing the processing demand on the computer in use. This vector based storage is important when it comes to animation, which is almost solely created with keyframes and advanced 'tween interpolation. When objects are made "editable", they are stored as individual points in space that link to create flat polygons. Although this takes more space digitally to store, objects can be modified with more flexibility once editable, and this is essential for modelling. In order to view an animation that has been created in Cinema 4D, one must first allow it to render. This a lengthy process which involves algorithms tracking light through the scene and calculating a colour for each pixel of an image. The final product is a single or series of raster image(s), which can then be imported into Adobe Photoshop, Adobe After Effects, Adobe Premiere Pro, Sony Vegas, Final Cut Pro, etc.

Although the two applications operate in different dimensions, both make use of vectors to store shapes and paths. This is important in animation software in order to maintain high quality when saving projects, i.e., to stay lossless. The final product from Flash tends to be a combination of raster and vector imagery, whereas Cinema's output is always in raster form.

Animation Technique

Flash animators are most likely to use a frame-by-frame animation model. This means that each frame of the animation is drawn individually. An effect called onion skinning may be used so that they're able to faintly see the previous few frames, which can help enormously in creating smooth-playing animation. Software 'tweening is also available in a few different forms, including motion 'tween and shape 'tween. By creating two keyframes well separated on the timeline, and then adding a 'tween, one can create very smooth movement. The shape 'tween also allows animators to morph between different shapes, by interpolating the movement of vector anchor points, but the effectiveness is not always acceptable.

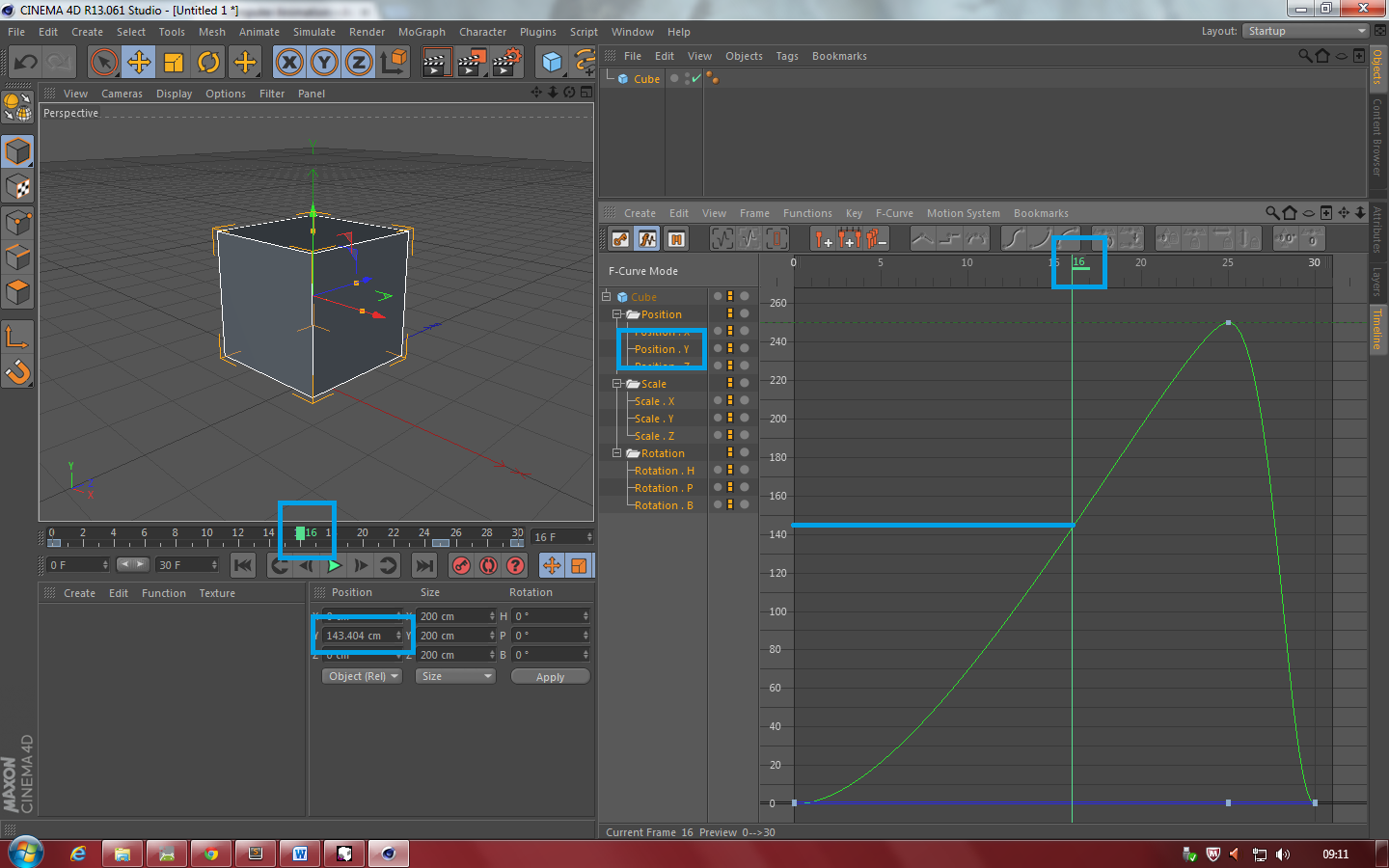

The power of keyframing shown in Cinema 4D. After the keyframes have been recorded, the program automatically creates a tween using Bézier interpolation, but this can be changed to linear interpolation, for example, if desired.

The power of keyframing shown in Cinema 4D. After the keyframes have been recorded, the program automatically creates a tween using Bézier interpolation, but this can be changed to linear interpolation, for example, if desired.

Animation in Cinema 4D is entirely keyframe-centric, making no direct use of frame-by-frame animation. Keyframes are very easy to create, and the use of interpolation makes smooth movement very easy to achieve. Cinema 4D uses f-curves to represent the change in a variable. The image shown on Assignment 1 uses the movement on the x-axis to show change, but hundreds of parameters can be animated similarly. The f-curves can be altered using vector like anchors and handles, and doing so can yield very good results. For basic animations using shapes in abstract settings keyframes every 30 frames may be sufficient, but for character animation, in feature-length films particularly, more would be needed.

Alternative Uses

Both of the packages have uses other than what many consider to be their intended application. For example, Flash can be used to create rich web content that cannot be created with nearly as much ease or speed when using the HTML5 and JavaScript alternative. This includes games and video players that can be highly customisable, as opposed the HTML5 <video> element, for example. Many of the simple games available on the web today are still built using flash, and the use of Flash puts a lot of power into the hands of the developer. Flash is also used because of its capabilities which haven't been implemented in JavaScript, for instance, due to security concerns. This includes the use of small, potentially invisible, Flash object that allows text on a web pages to be copied to the system clipboard. As Flash is also able to read the data stored on the system clipboard, such functionality has not been implemented, even with the introduction of HTML5. Users could potentially have personal details on their clipboard, which would then be visible to any website they visit.

Cinema 4D offers powerful animation tools, but it can also be used for complex 3D modelling and scene design. Many artists find the easy-to-learn UI and effective rendering attractive in terms of being able to quickly create detailed and eye-catching pieces. The BodyPaint 3D extension for Cinema brings common modelling and texturing tools present in other similar packages into the hands of the user. This is incredibly useful when creating models of organic shapes, that would otherwise be difficult and tedious to build.

System Requirements

The system requirements for both of the applications are listed below, as stated on the developers' respective websites.

Adobe Flash Professional CC 2014

| Component | Minimum Requirement |

|---|---|

| Processor | Intel Pentium 4, Intel Centrino, Intel Xeon, Intel Core Duo (or compatible), AMD Athlon® 64 (2 GHz+) |

| OS | Microsoft Windows 8.1/8/7 (SP1) (64 bit) or Mac OS X 10.7/10.8/10.9/10.10 (64-bit) |

| Memory | 2 GB (4 GB recommended) |

| Storage Space | 4 GB for installation |

| Display | 1024 × 900 (1280 × 1024 recommended) |

| Other | QuickTime 7.7.x recommended |

| Internet | Required for software activation, validation of subscriptions, and access to online services |

Maxon Cinema 4D R16

| Component | Minimum Requirement |

|---|---|

| Processor | Intel Pentium 4, AMD Athlon 64 |

| OS | Microsoft Windows 8.1/8/7/Server 2012 (64 bit) or Mac OS X 10.7.5+ |

| Memory | 4 GB |

| Storage Space | 7 GB for installation |

Cost

Both of the applications are professional grade, and come with price tags that suggest as much. Since the release of Creative Cloud, Flash Professional has been available on a subscription basis for £17.58 per month, if a year subscription is agreed, bringing its cost to £210.86 per year. Cinema 4D is available in a number of versions. Including VAT, a license for the entry-level package, Prime, costs £720. In contrast, a Studio (top-level) license costs £3,120.00.

For both of the packages more complex plans exist for companies, educational institutions and individuals eligible for discount.

Workflow

Cinema 4D, for a number of reasons, makes quick creation of interesting scenes very easy. For this reason, I decided to create a image of one thousand different coloured cubes falling onto the ground and spreading outwards, using the physics simulation built into Cinema. Below is a series of images showing the process.

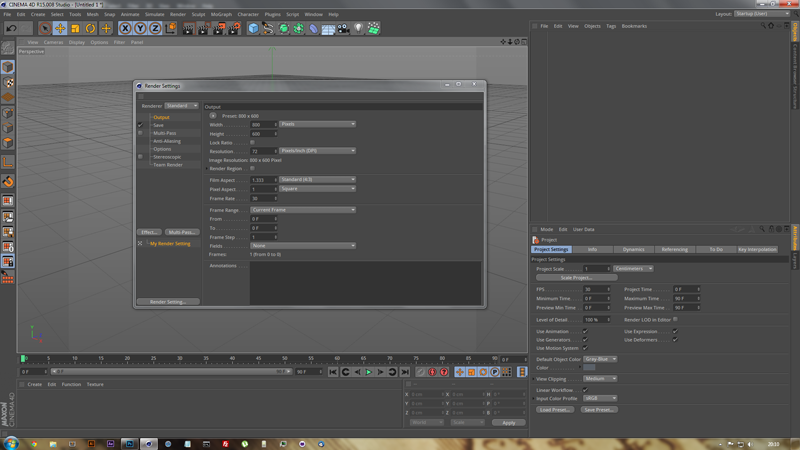

Maxon Cinema 4D R15 Studio after being opened, showing the Render Settings window.

Maxon Cinema 4D R15 Studio after being opened, showing the Render Settings window.

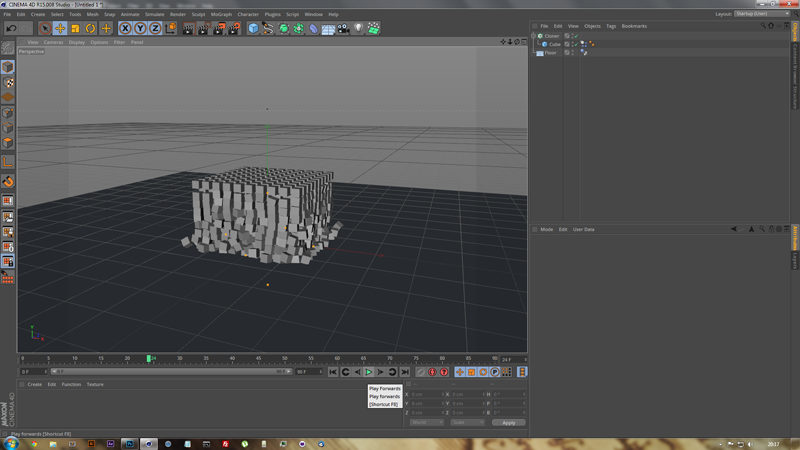

A cube, cloned in a larger 10 * 10 * 10 formation, with each individual cube given a dynamics body tag. They impact the floor, which has a collider body tag attached, and spread outwards.

A cube, cloned in a larger 10 * 10 * 10 formation, with each individual cube given a dynamics body tag. They impact the floor, which has a collider body tag attached, and spread outwards.

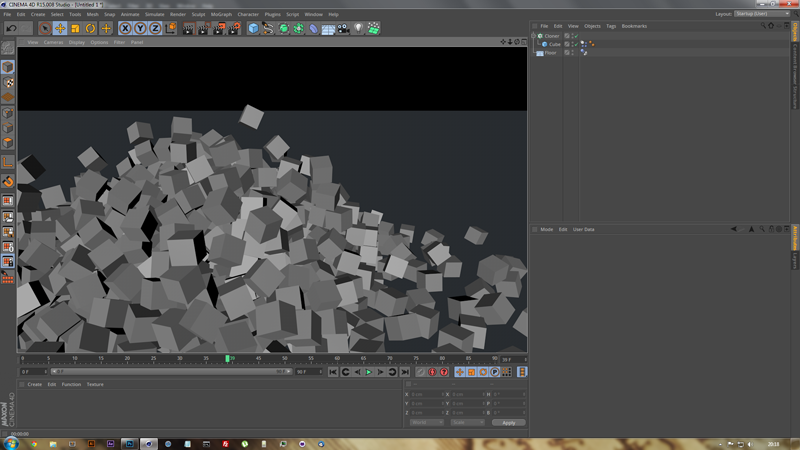

The cubes a few frames later, shown after a default render.

The cubes a few frames later, shown after a default render.

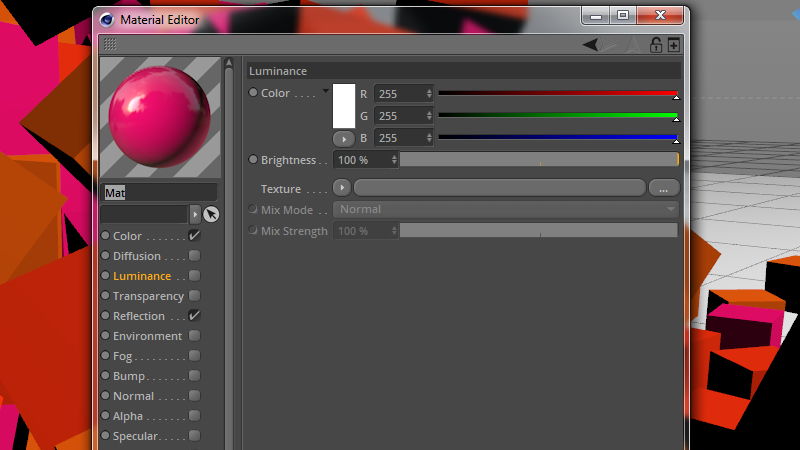

The material editor, showing a pink, reflective material. Shown to the left are some of the attributes that can be adjusted for materials.

The material editor, showing a pink, reflective material. Shown to the left are some of the attributes that can be adjusted for materials.

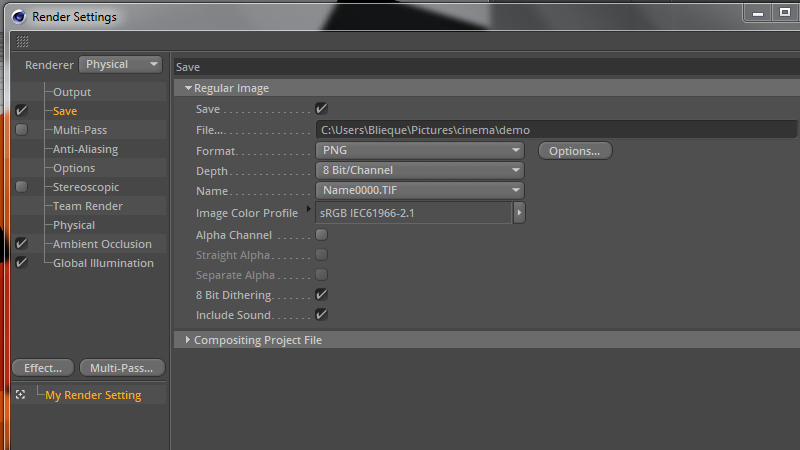

The render setting window, showing a full output path, PNG format selected, the physical renderer selected, and AO (ambient occlusion) and GI (global illumination) effects added.

The render setting window, showing a full output path, PNG format selected, the physical renderer selected, and AO (ambient occlusion) and GI (global illumination) effects added.

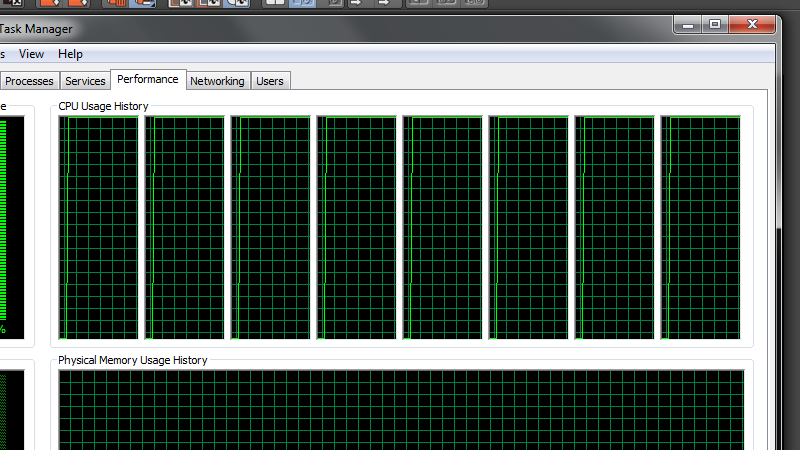

The process of rendering the scene took over 15 minutes, and pushed eight 4.3 GHz cores to their max. Hardware acceleration has not been implemented into Cinema, so it's forced to render using the CPU.

The process of rendering the scene took over 15 minutes, and pushed eight 4.3 GHz cores to their max. Hardware acceleration has not been implemented into Cinema, so it's forced to render using the CPU.

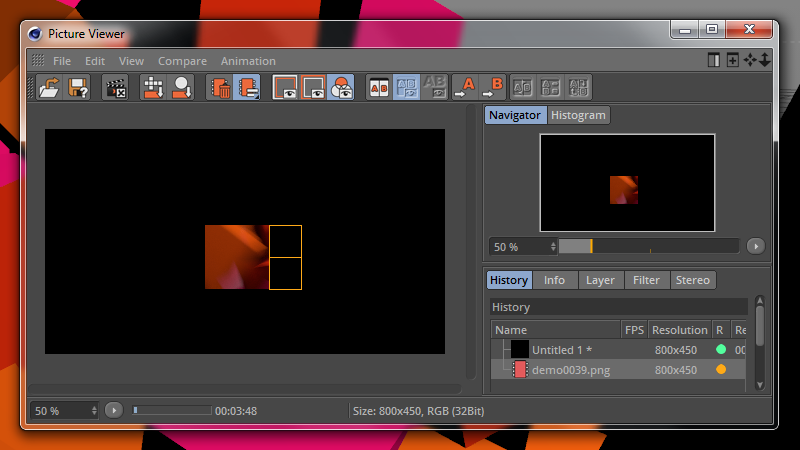

A render in progress.

A render in progress.

The 256 colours picked by Photoshop for PNG-8. The final was in fact saved as a PNG-24 image.

The 256 colours picked by Photoshop for PNG-8. The final was in fact saved as a PNG-24 image.

An image to show the effect of dithering when using a limited palette; 256 colours in this case.

An image to show the effect of dithering when using a limited palette; 256 colours in this case.

To Conclude

Overall, Flash Professional and Cinema 4D both meet different criteria, and both do so well. Personally, I prefer using Cinema 4D as I fell more acquainted with it's interface and I feel the output is more relevant to today. With Flash I feel as though the work is unnecessary, as Flash is primarily used on the web and in mobile app development, both of which fields I feel there are better alternatives in. The latest release of Flash Professional is currently CC 2014, released in late June. Cinema 4D R16 was released in early September of the same year, 2014.